Getting stuck sucks. There’s no way around it. Whether it’s not being able to find the missing semicolon or having trouble understanding this new library, being stuck is one of the most frustrating parts of programming. That being said, it’s also one of the most important aspects of programming. A programmer who can surmount these roadblocks is worth their weight in gold.

I’ve found that students don’t always know how to get unstuck. Which is understandable; getting unstuck isn’t a skill taught in a lot of CS programs. But here’s your chance to prevent that. I’m going to provide 4 levels of getting stuck, from basic to advanced, then methods for getting unstuck. Some of these levels you may already know how to tackle. Others you may not.

Level 0: My Code Won’t Compile!

This is the lowest, and most common way people get stuck. Their code doesn’t compile or something small doesn’t work, say a wrong output or an unexpected segfault/exception. Basically the issue is at the level of code execution, not conceptual or theoretical.

Generally people have decent strategies for this level. If your code doesn’t compile, generally the compiler will have some decent error messages which can help you. I often comment out code and see if the compiler error goes away.

For runtime errors, Some people use debuggers like gdb (which are actually a lot cooler than your CSO prof made them out to be!). Others, like myself, use print statements. Print statements are nice because they allow you to see the flow of your code, even in languages like C that don’t have exceptions. I use numbers a lot of the time so that you can see when the code halts:

char* file_content = read_file();

printf("1\n");

char* first_entry = get_first_entry(file_content);

printf("2\n");

int first_number = parse_int(first_entry);

printf("3\n");

If the output is:

1

2

Then you know that the bug is probably in parse_int.

Another good strategy to learn is to write small tests. In some

languages you’re lucky enough to have a REPL or Read Eval Print

Loop. That’s the prompt that pops up when you type in python to your

Terminal. REPLs are great ways to test out small assumptions. For

instance, say I forgot how to get the length of an array in Python

>>> arr = [1, 2, 3]

>>> arr.length

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

AttributeError: 'list' object has no attribute 'length'

>>> arr.len

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

AttributeError: 'list' object has no attribute 'len'

>>> len(arr)

3

And hey, cool! Now I remember.

For languages that don’t have REPLs, like C, you can write a small program and check. I have a folder called scratch on my computer where I test out small programs.

For instance, my scratch.c file currently has a small program

testing out how to read items from a directory in C. When I was

writing ls for my Operating Systems course, I wasn’t super clear on

how that worked. Instead of blindly forging ahead and trying to get

the code right in the context of the complicated lab code, I decided

to just write a small test that read from a directory. That way I was

able to understand that code in isolation before applying it to the

larger context of ls.

And sure, you can always look up the answers to these small questions on StackOverflow, but there’s something to be said about testing your hypotheses. For one, if you’re ever without an internet connection and writing code, you’ll be able to make progress. Second, you’ll be able to reason through your code a little better. If someone asks you a question, instead of just directing them to StackOverflow, you can write a little test and find out. Plus typing a few lines in a REPL takes less time than searching on Google, finding a StackOverflow answer and reading it.

Level 1: I Don’t Understand This Error

The next level can be described as basic conceptual problems. For instance, say you need to read a file into memory with Python. Where would you go to learn such a thing? Who you gonna call? StackOverflow!

Ah StackOverflow. The most worshiped of programming sites. And for good reasons. It’s an incredibly useful site. Most people restrict themselves to just reading it, so that’s what we’ll discuss for this level.

When reading a StackOverflow post, it’s important to keep a mental checklist. Here’s what I keep on my checklist:

- Is this solution up to date?

- Does this solution actually solve my problem?

- Is there some specific precondition in this question that doesn’t apply to me?

- Why might I not want to use this solution?

To give an example, let’s walk through a simple question. You have an array of values in JavaScript. You want to check if a value is in the array. Google around, you find this post.

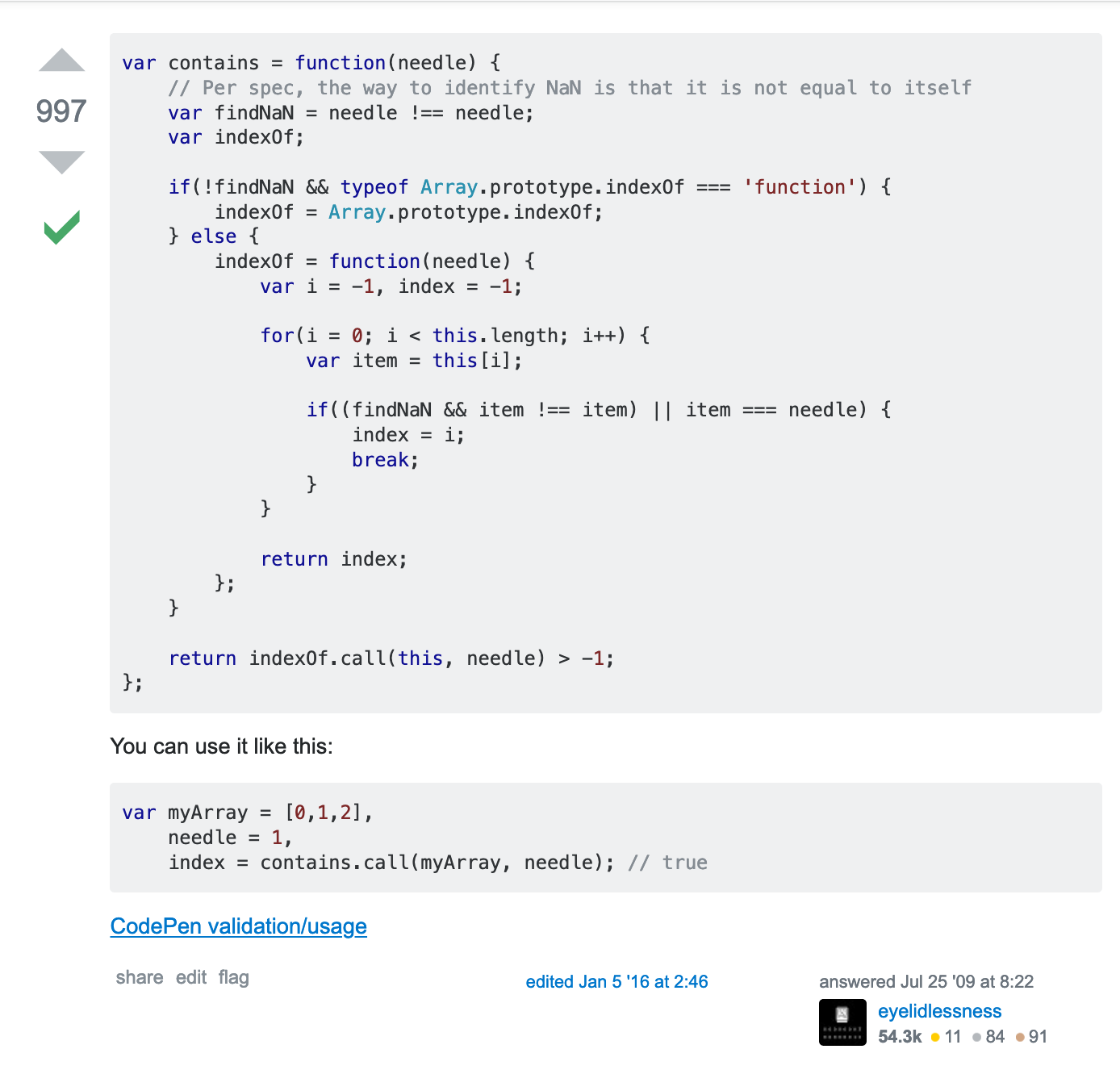

Looking at the first answer, we see this:

Going through our checklist, we notice that the answer is from 2009. Sure, there’s been some edits since then, but the core code is still over 10 years old. Hmm, maybe that’s not the best option.

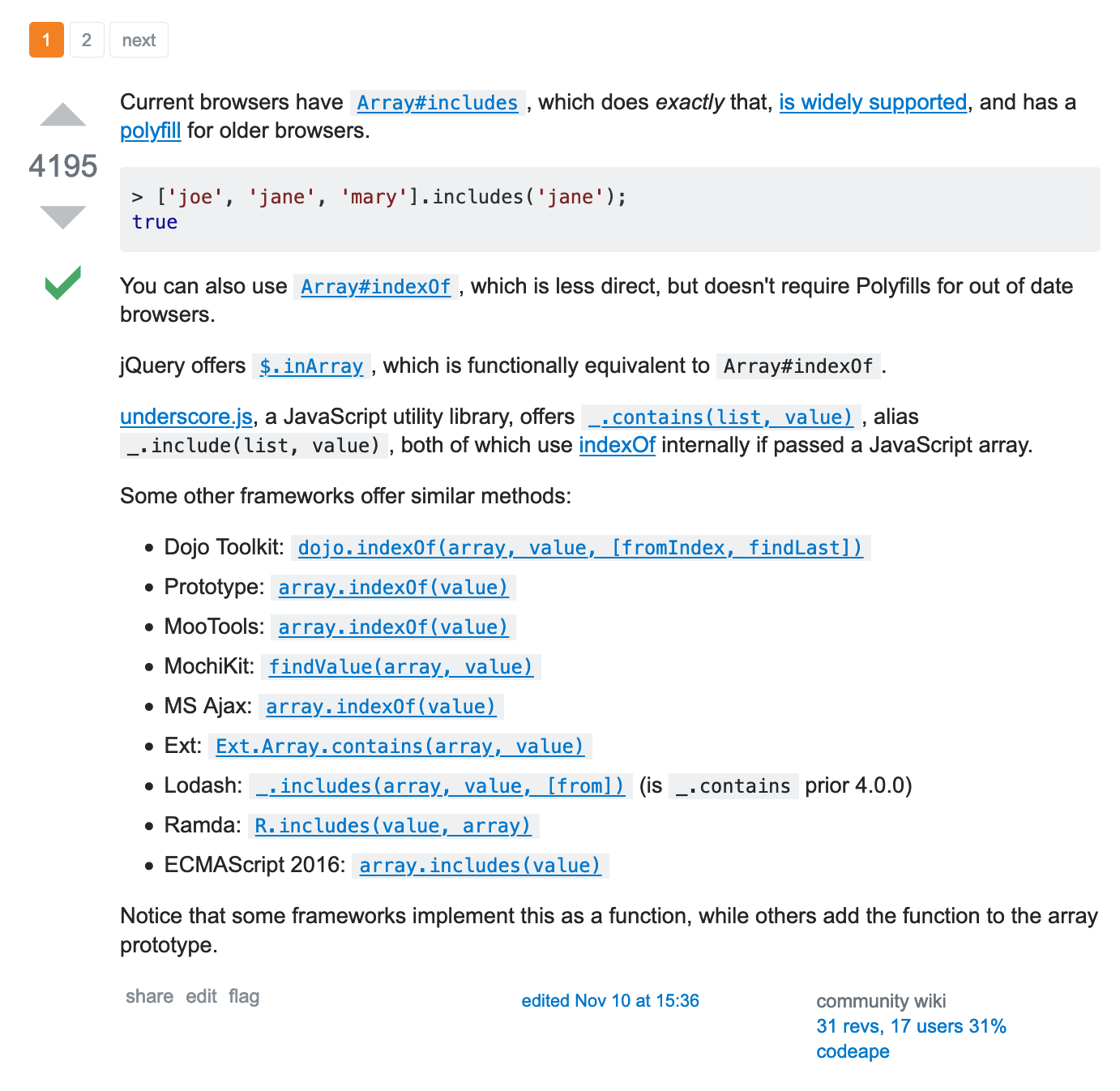

In fact, most of these answers are 10 years old. So maybe this isn’t the best post. Let’s go to another post. Reading the first answer, we see:

This is pretty good! The answer was last updated in November of this year, there’s a few different options given and the post has plenty of upvotes so people have found it useful.

Reading the post, we notice that there’s a built in Array#includes

function that does exactly what we want. Great! This solution is up to

date, it solves our problem and it doesn’t have any unnecessary

preconditions.

But why might we not want to use this solution? If we read a little

further, we notice that Array#includes may not work for older

browsers. Depending on your situation, this might be true. Many

companies still support old browsers. If it is, then maybe we should

consider the other options given in the post, such as using

Array#indexOf or using a library. Of course, you should cross

reference each of these options in turn with the checklist.

There’s definitely other things you should add to your checklist such as number of upvotes, comments, security concerns and even code style. But that’ll come with practice and experience.

I’ve been talking solely about StackOverflow, but there’s other helpful resources, such as GitHub issues. GitHub issues are problems opened on GitHub repositories for a given library or language. GitHub issues are great for fixing problems with newish libraries or cutting edge language features. For instance I use issues for problems with front end libraries because front end development moves so quickly that the likelihood I’ll get a good, up to date answer on StackOverflow is next to nil. Likewise, if I were using Rust’s nightly language builds and ran into a weird error, I might look on Rust’s GitHub issues page.

One quick tip is to search through closed issues as well. Often these will have your solution.

Of course sometimes you run into an issue with what appears to be five million comments, ending with “any updates on this issue?” (*cough* Rocket *cough*). That sucks.

There’s other niche sites that are useful. For instance, Server Fault for system administrator problems, Emacs StackOverflow for emacs issues, and on occasion Reddit can be useful.

Please don’t copy code directly from StackOverflow. For one, it’s lazy

and doesn’t teach you anything. Typing out code forces you to go

through it word by word (or lexeme by lexeme I suppose). You can learn

a surprising amount by just transcribing. Also the naming and overall

structure of a snippet might not work with your existing code. If a

snippet uses a names variable when you’re dealing with colors, it’ll

be super confusing for any future developers.

Level 1.5: This Answer Doesn’t Entirely Work

Unfortunately it’s all too common that a StackOverFlow answer doesn’t work completely. Unless you happen to stumble upon a post that exactly gives you the answer to your specific question, you’ll probably end up in a situation where one post on SO will give you 40% of the answer and another post will give you another 30% and you have to kinda futz the last 30%. You can and should get good at futzing. Futzing basically means making leaps of logic and trying different approaches. This is where version control comes in handy. You can commit your existing code, try a new approach, then roll it back if it doesn’t work.

Common techniques in futzing include using different package versions, rewriting part of the code, and going back to Level 0 or local debugging.

Level 2: My Question Isn’t On StackOverflow

This is the big jump. This is what separates the children from the adults. If you dare to dip your toe into the vast, sometimes intimidating pool of knowledge that is StackOverflow and ask a question, you can reap some immense rewards.

StackOverflow has a reputation of being prickly and unfriendly. And sometimes that can be the case. But it’s a little undeserved in my opinion. If you follow the tenants of writing a good question, then you won’t face the wrath of StackOverflow. SO includes a great guide on writing a question. But really, it boils down to doing your due diligence in researching the topic and exhausting all possibilities before posting. Jon Skeet, one of the most legendary StackOverflow question answerers (over a million reputation points), has a post as well.

However if you do face some resistance or snark, it is good to push back, albeit gently and politely. A comment noting why your answer is not a duplicate or describing the problem in more detail will notify the responders that maybe they should take a second look.

In general it helps to be polite. You may be panicking and stressed and under a deadline, but that doesn’t mean you should be rude. I try to always end the question with a thank you and my name. It may seem overly polite or formal but I hope it endears me to anybody reading the question.

GitHub issues are great place to ask as well. Again, GitHub issues are more for cutting edge problems or specific libraries. Sometimes the project will have a template to fill out. These are great and you should do your best to follow it as closely as possible.

Sometimes I use GitHub issues if I’m trying to accomplish something but the documentation isn’t up to par. Even though it’s not technically a bug in the code, it’s a bug in their documentation. Which is equally important.

Level 3: How The F%$K Does This Library Work?

Ah yes, you’ve decided to use a library or maybe another codebase and the genius authors left no goddamn documentation. You need to figure out how it works before the assignment deadline/end of the sprint/bombs explode. This is where it gets real. This is where you need to learn how to read code.

Reading code isn’t easy, but it’s incredibly rewarding. It’s much much harder than writing code and equally as important. Much like how reading good prose helps you write good prose, reading good code helps you write better code. And reading bad code can help you understand what not to do. I’ll probably write a full post about this, since there’s a few strategies I’ve picked up over the years.

If I had to give a crash course on reading the source, I’d start by recommending that you clone the source code from GitHub or wherever it’s stored. Then use something like ripgrep to search through the code and something like fd or find to search through files. A good IDE can also do wonders. VSCode isn’t technically an IDE but because of language servers, it works as one. I also love JetBrains IDEs, which you get free with your NYU email. I use WebStorm for web dev and Intellij for Java/Rust development. You can also take notes on the codebase, either on paper or on the computer. I use org mode with urls, but that’s a little involved.

A great way to learn more is to build the code and play around with it. Try to tweak functions or add print statements. You can learn a lot that way.

This is a level that most people don’t even think to tackle. I myself only started to read other people’s codebases to solve my bugs within the last year or two (I credit a wonderful interview of Joe Armstrong, the creator of Erlang for the inspiration). But when you think about it, the source code is the only truly accurate and up to date documentation. Plus once you learn to read code, not a lot can stop you. Any library can be adopted. Any bug can be pinpointed with enough code reading.

Plus there’s nothing better than opening a GitHub issue that provides the exact issue with line numbers and everything. The maintainer will probably like that a lot more than a “help my code doesnt work!!!”.

Level 4: This Library/Compiler/Tool Is Broken

You’ve gone through level 3 and read the damn code. But wait! You’ve realized that there’s a bug. What do you do? Fix it!

This is the truly enlightened approach. Have a problem with a library? Fix it your damn self! Not only will you fix your problem, you’ll get some open source street cred. There’s nothing like saying you’ve contributed to the TypeScript language or the Postgres database, or whatever.

Again, this isn’t easy. But getting used to reading and eventually contributing to massive codebases is an extremely valuable skill. A lot of work in a large tech company is precisely that. If you can learn these skills now, you’ll be well prepared for working in the industry.

If you want to contribute to an open source project, reach out to the maintainer and ask for some help. They’ll generally be accomodating—after all who would turn down free labor? Try to pick a simple task. Don’t attempt a major feature on your first try.

Once you have a task, find the minimal amount you need to learn of the codebase to make some progress. Try tweaking a little bit of code, then compiling/building and seeing what happens. Don’t be afraid to go back to the maintainer and ask for help.

Other

There’s certainly a lot more ways you can get stuck, but I believe that these five (and a half) ways are the main tiers. I’d say an average CS student can handle levels 0 and 1, a good CS student can tackle 0, 1, 1.5 and maybe 2. A solid programmer can definitely handle level 3 and a fairly good programmer can do 4. Truly top tier programmers can take level 4 to the next level and build libraries/languages/tools that solve their problems. If you can do that, then truly nothing can stop you.

I don’t expect everybody to get to the top levels immediately, but if you can jump up a level, it’ll make a huge difference in terms of how you approach programming and what you can accomplish on a daily basis.